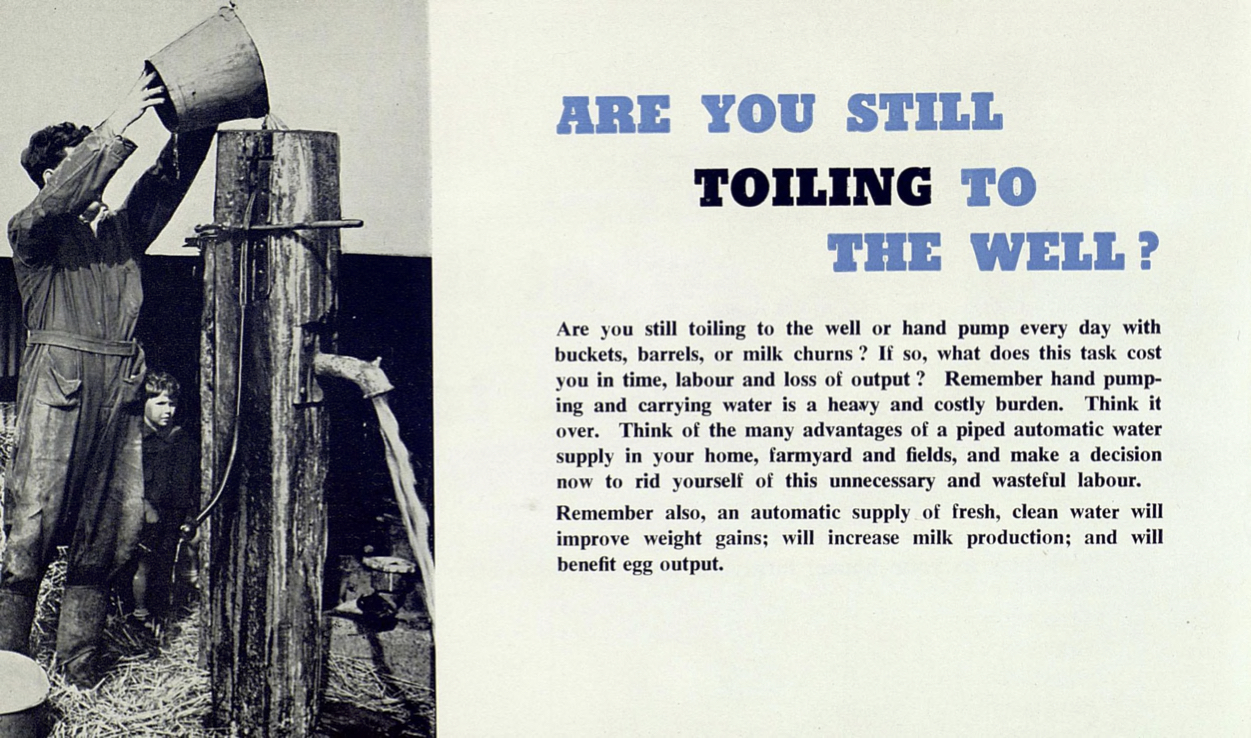

Group Water Schemes (GWSs) developed in the mid-20th century in response to the lack of piped water in rural Ireland. Before the 1950s, many hauled water with buckets and barrels, devoting significant time and physical labor to meet daily water needs. Topography and a dispersed rural population made these areas difficult to reach with the public supplies that serviced urban areas.

For many this situation was untenable. In the mid-1950s, following the rural electrification schemes of the previous decade, group and regional water schemes were increasingly considered as viable strategies to deliver water to rural areas. In 1957, Father Joe Collins developed the first GWS in Oldcourt. However, lack of funding curtailed early efforts to expand on his example. In 1959, piped water supplied only 9% of farms and only 12% of rural households. We have created timelines of this history from the 1950s to the present.

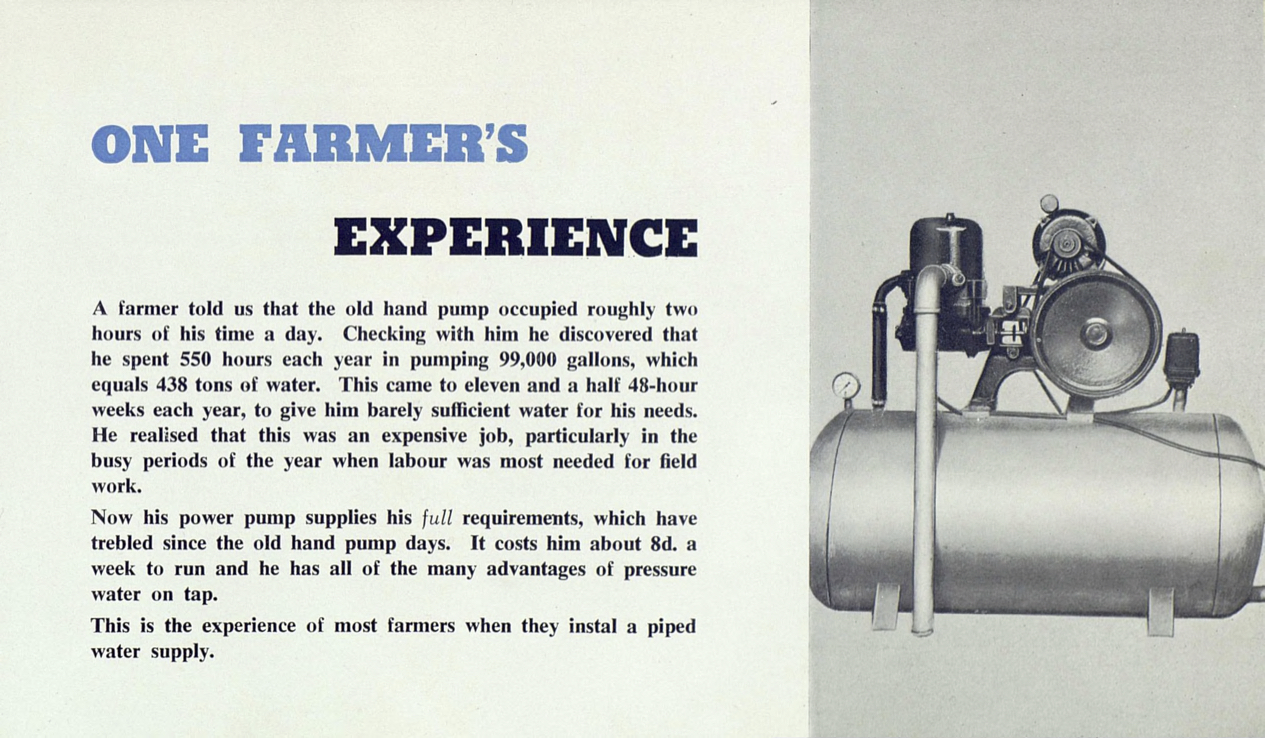

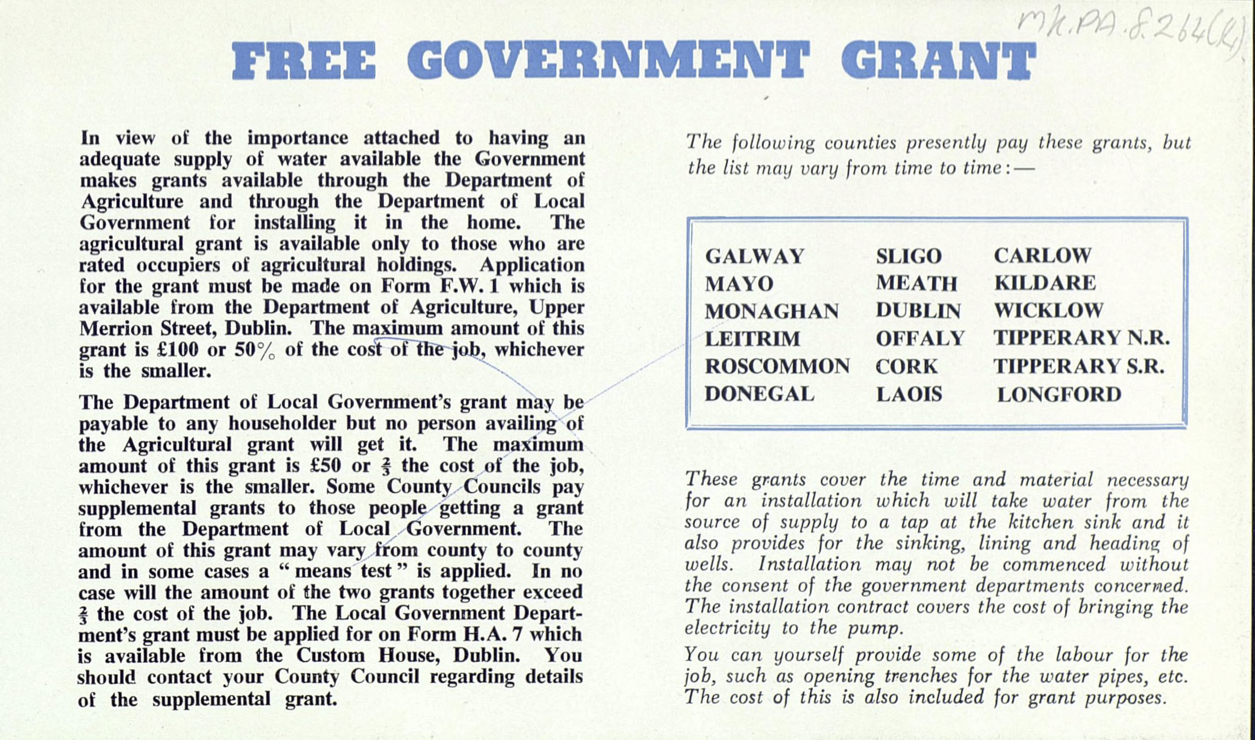

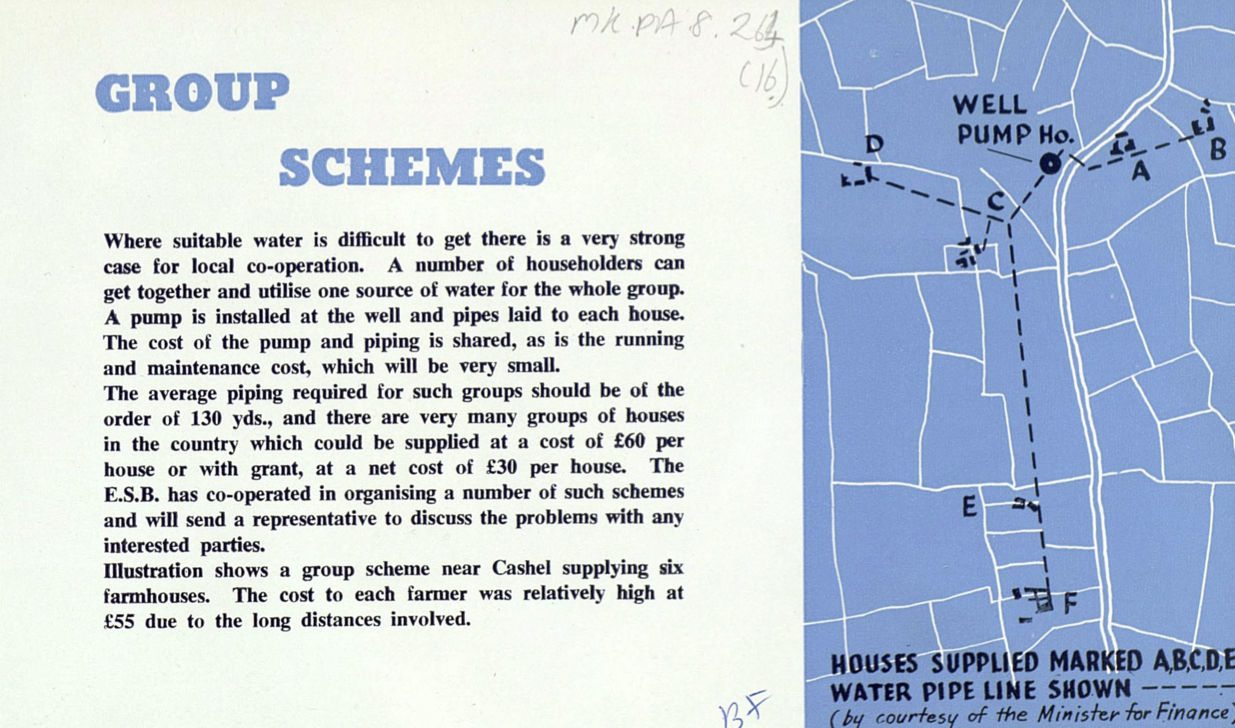

Campaigns developed to extend the delivery of piped water to improve rural quality of life but they faced resistance from farmers who feared increased costs. Different groups, such as the Irish Countrywoman’s Association (ICA) and the Electricity Supply Board (ESB) charted campaigns to convince farmers and others that piped water had many benefits, particularly through private wells and groups schemes. Some examples of these arguments about an increased quality of rural life and better yields from dairy cows are in this pamphlet from the ESB.

From the ESB Archives

Farmers’ concerns eventually gave way to the economic benefits of piped water and local cooperatives used these government grants to develop schemes over the next several decades. GWSs developed first in regions looking to attract rural tourism in the 1960s. By the 1970s, however, Ireland had been included in the European Economic Community. New pressures to develop industrial-scale agriculture helped drive new interest in developing GWSs.

Despite the state’s initial investment, GWSs operated outside of state oversight until the late 1990s and early 2000s. This would change when the EU would see the Irish State as responsible for poor water quality, even in private suppliers. Reports in the 1990s showed that many supplies were failing water quality standards, and by the end of the century, it was clear that the EU was going to require the Irish government to take notice. Thus, since 1998, the Rural Water Programme has funded water treatment upgrades, research, and restructuring of GWSs to help address these concerns. Moreover, in 1997, the National Federation of Group Water Schemes (NFGWS) was established as a representative body for GWSs and has advocated for increased funding and research.

GWSs are uniquely situated within the Irish water sector given their adaptations over the past 20 years to economic, political and environmental pressures. GWSs bundled, amalgamated, and upgraded. They entered into 20-year Design, Build, Operate (DBO) contracts, with significant funding from the Rural Water Programme. Partnering with industry and academia, they have engaged in pilot projects to implement innovative strategies to protect source water, identify leaks, and manage the supply networks.

Through these changes, GWSs have also sought to maintain their identity as community water suppliers while also professionalising parts of their operations. Some GWSs, with the help of the NFGWS and government funds, have hired part-and full-time staff and managers. At the same, they have continued to rely upon local knowledge and labor, many volunteers have participated in training in topics such as quality assurance. For example, in one scheme we visited, while meter readings could be automated, this GWS prefers reading the meters by hand, allowing them to annually spot check connections and to be seen and known by their water users.

GWSs have not navigated these developments in a vacuum. Their recent history is even more interesting given significant restructuring to the public water system. In 2014, the public water supply, which had previously been managed by local authorities, was consolidated into the semi-state utility called Irish Water. Irish Water introduced water charges and metering into the public water supply (both would later be reversed), techniques that GWSs had already long been using as part of their water delivery. A microcosm of changing relationships to water, infrastructure and the state, GWSs have much to show us about broader happenings in our economy, culture, and environment.