In September, we went to the National Ploughing Competition, an event filled with cows, ploughs, and lots of farm equipment. Why would we, a project focused on community-managed water supplies in Ireland, go to an event catered to this industry?

Group Water Schemes (GWSs) in Ireland and located in predominantly rural areas which are dominated by agriculture. Efforts to manage water supplies in these places requires understanding agricultural demands and practices, particularly where farmers use water from supplies and where their agricultural activities can negatively impact the quality of GWSs source waters. But agriculture is more than an economic activity. It is an important part of rural life and many rural identities. We went to the ploughing competitions to better understand – in a small way – how water, agriculture, and rural living, are imbricated with one another.

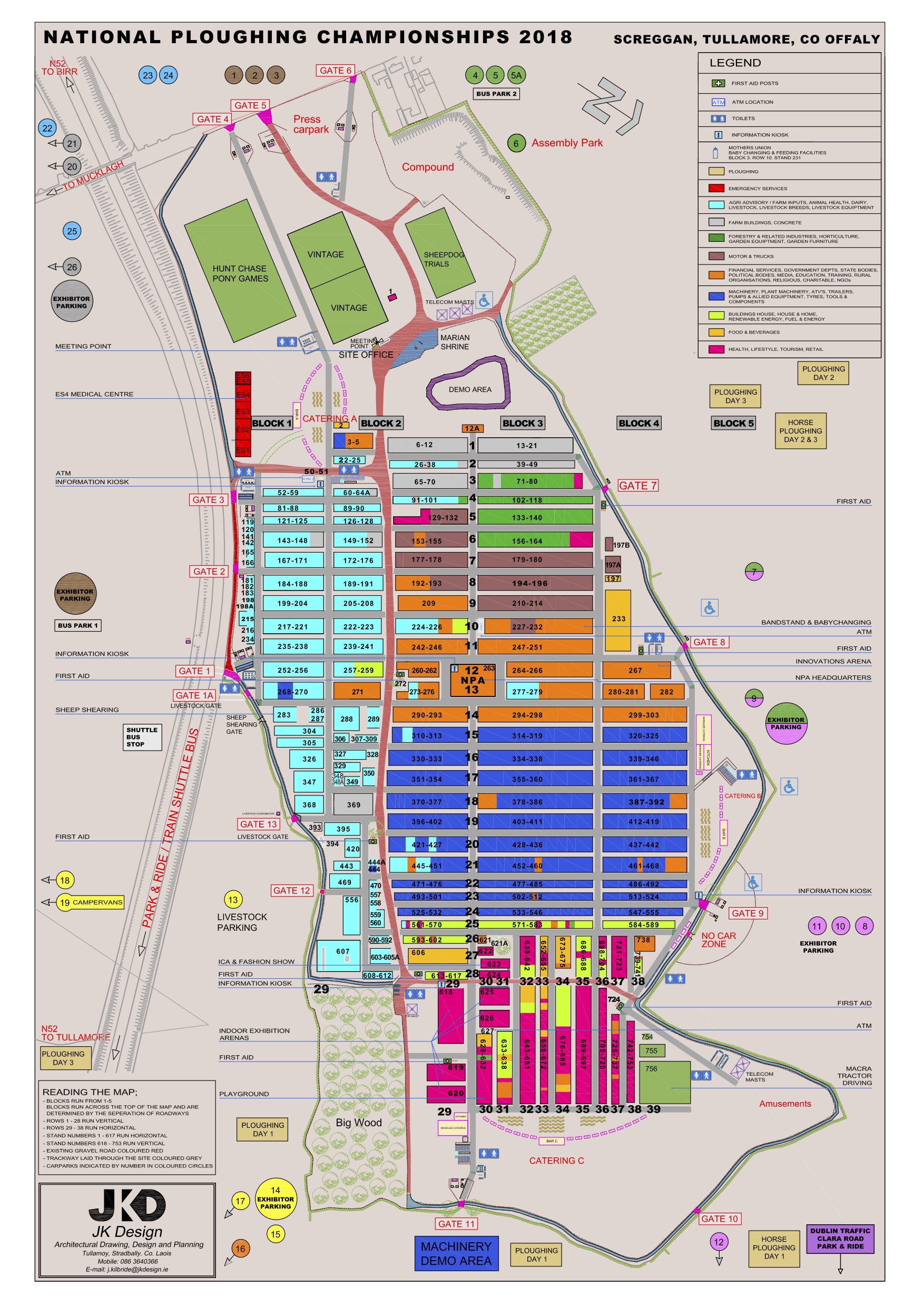

The National Ploughing Competition is an annual event that was held over three days in Screggan, Co. Offaly. It drew 1,700 vendors and estimates of just under 250,000 visitors this year despite one day being rescheduled due to treacherous weather conditions and damaging winds. While the event focuses on rural life, it is widely subscribed to across Ireland.

The national news media, RTÉ, broadcasts from the event on TV and radio; the train I took from Dublin’s Heuston Station and bus from Tullamore Station – both modes of transport put on specifically for this event – were packed with lively competition goers.

The event itself is vast. The main grounds are gridded into a city, with events and vendors grouped thematically. To the edges of the main grounds are the ploughing competitions, where tractors and their drivers competed against one another in a persistent rain that lasted all day. Tractors are classed by vintage, county and the age of the driver and the competitions are closely monitored by officials of the National Ploughing Association. Even in the rain, small crowds gathered to watch.

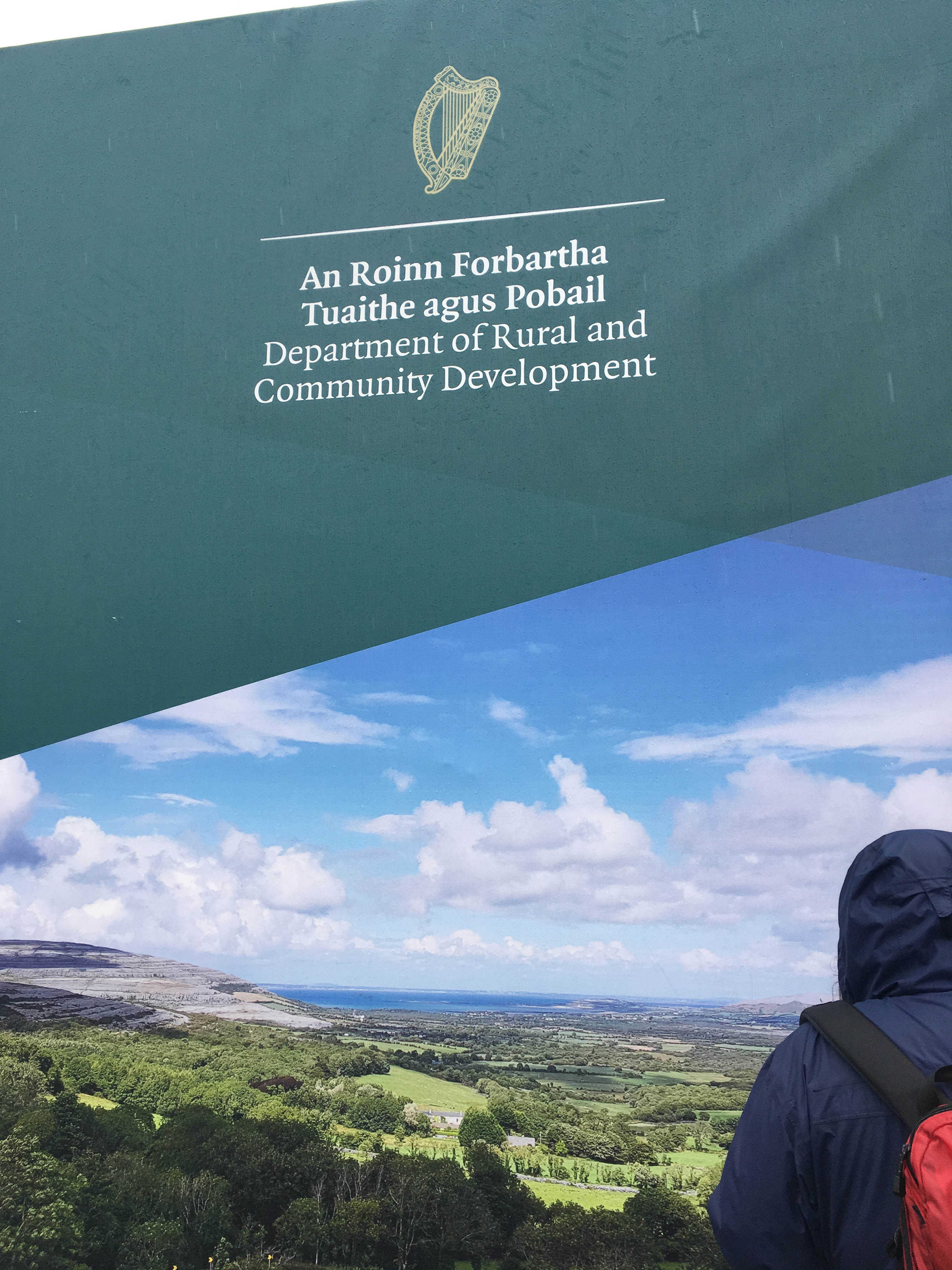

The event caters to interests beyond ploughing. Abundant choices for shopping (cars, clothes, and GAA sports equipment), country music, and fair food were tucked among commercial vendors with products catered to the agricultural industry. Political parties and government agencies handed out literature about their activities vied for attention with vendors that catered to Ireland’s largest agricultural sectors: beef and dairy.

Vendors had a lot on offer: pamphlets described nutrient supplements to increase cow gut-health and weight gain, animal pens show-cased bulls whose genetic material was for purchase, and digital technology trackers were demoed to show how heat sensors could track cows during mating. Much of the event centred on cows.

Many of the vendors specialized in water services to increasing water delivery to animals and reduce the costs of water delivery. Water is central to agriculture; its benefits on herd size and dairy production were central in the justifications of group water schemes and rural water delivery more generally. These issues surrounding water have not gone away.

Vendors catered to a whole set of concerns that embroiled agricultural policies and water delivery. Many of the vendors I spoke with were providing technologies, goods and services that sought to deal with two issues: 1) a push to expand herd sizes in the last decade which requires farmers deliver more water to animals and 2) regulations that restricted animals from waterways and required farmers find alternative water sources for their animals, namely pumping water into water troughs.

“The bigger the herd…the bigger the pipe size”

Philmac, a company that supplies agricultural pipes, justifies its business in a dependent relationship between herd size and pipe size. Pipes with wider diameters, for Philmac, allow more water to be more quickly supplied to more animals. Philmac advocated that farmers switch from ¾ inch pipes to 1 ½ inch pipes—allowing water troughs to be filled more quickly. Other companies took a different approach to supply water, offering their flow rates as faster, their fittings and connections stronger, with demonstrations tanks and text pipes.

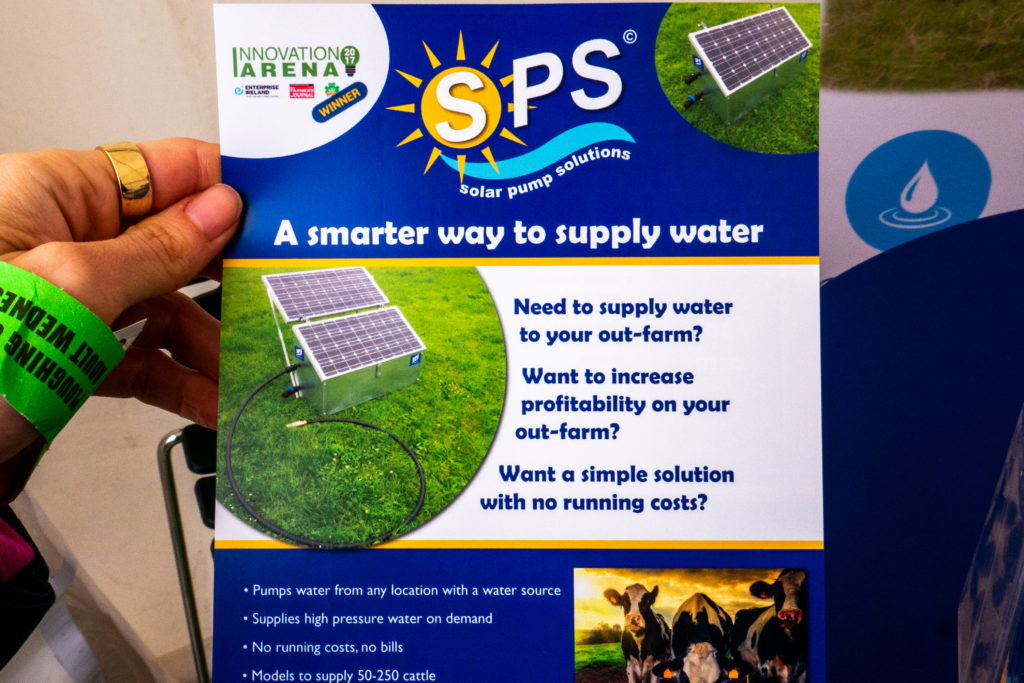

To get water into the pipes, farmers need pumps, often supplied by separate companies, when they are pumping water directly from water sources.

These pumps may also need to be powered; in the case of Solar Pump Solutions, solar panels are used to deliver the power necessary to pump water to the animals in areas without electrical hookups. As with other technologies, these products are marketed to lower costs and increase the profitability of animal-based agriculture. And, like many others, featured cows on their brochures.

Water has to be piped somewhere. Hence, cement vendors dedicated exhibits to displaying water troughs for the water.

Water supplies do not always come from waterways. In addition to being connected to public and group water mains, some farmers may choose to develop their own supply from a well—something that anecdotally was mentioned as a growing concern following this year’s drought and water restrictions. Ellis Water Well Drilling bills its services as a cost-saving measure to supply farms with more water. On several of its leaflets and signage, the company explains to prospective customers how to access government grants for wells, when meeting certain requirements.

All of these vendors were talking to people when I arrived at their stands. I found prospective customers eagerly discussing different options, looking at equipment, and taking brochures and other information. While not wholly indicative of the application of these services on farms, there was certainly interest in how to improve water management in animal-based agriculture. For our work and interest in source water quality for drinking water supplies, how water and land are managed, and if and how this translates into agricultural pollution in source water, is an important.

So why did we go to the ploughing competition? The event offered a unique look into the way policies—agricultural and environmental – intersect with real-world practices and industries and manifested at this major cultural event for rural Ireland, all of which have ramifications for the management of water supplies in Ireland.